In maintenance, just as in sports, you don’t know whether you are winning or losing unless someone keeps score. The “score” for many companies is the Mean Time Between Repairs (MTBR). Unlike in a ball game, the MTBR score is subject to definitions and interpretation. Let’s take a look at keeping score and how a simple number can become complicated.

Other acronyms may be used to imply the same premise as MTBR. MTBR has been variously labeled as MTBF (Mean Time Between Failures), MTBC (Mean Time Between Changes), MTBM (Mean Time Between Maintenance) and, no doubt, many others. There may be subtle differences between these variations on the theme.

Using MTBR to track equipment reliability is an old idea. It was applied to refinery pumps in the early 1970’s and was described in reliability textbooks from the 1960’s but was probably used prior to those instances. Today, “What is your MTBR” is not an uncommon question during roundtable discussions at equipment conferences. Once a number is given, someone is likely to top it. So, what is MTBR and how is it calculated?

In perhaps the most official definition, Process Industry Practices (PIP) defines Mean Time Between Repairs as: “The most common measure of operating reliability, typically stated as the average operating calendar time between required repairs for a particular piece of machinery, type of machinery, class of machinery, operating unit or plant. MTBR is not Mean Time Between: (a) Failures, (b) Planned Maintenance, or (c) any other categorization of shutdowns. MTBR calculations include Repairs due to (a) Failures, (b) Planned Maintenance, or (c) any other categorization of Repair events.”

MTBR appears to be such a simple and straightforward statistic that many operating plants use it to track reliability of rotating equipment such as pumps, motors and compressors. There is a growing trend to use MTBR as a benchmark for making comparisons between operating plants and even between competing companies. Another trend is to include MTBR goals in maintenance or supply contracts. Unfortunately, in spite of the PIP definition, MTBR is not sufficiently well defined to be used for benchmarking or contractual obligations.

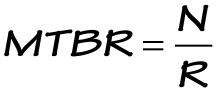

The actual equation for computing MTBR is obvious, simple and universally accepted:

The general idea is to divide the number of machines, N, by the number of repairs, R, in a given period of time. The controversy begins with the definitions of N and R; those definitions can vary considerably.

Although PIP is widely referenced, PIP definitions are somewhat general in nature and intended for broad categories of rotating equipment. N is the number of active machines and R is the number of maintenance tasks that require shutdown. Active machines include the spare, or standby. Nearly every shutdown counts as a repair, including inspections and equipment upgrades. PIP recommends that MTBR should be computed for each category of equipment.

PIP suggests dividing the pump population into groups such as centrifugal/reciprocating, single stage/multi-stage, API/ANSI, sealed/sealless, etc. Each group could include a wide range of sizes, designs and services. In practice, most users make a few simple rules about which pumps will not be counted and then place the rest into a few basic groups such as centrifugal (sealed), centrifugal (sealless) and reciprocating. Small pumps, such as chemical injection pumps, are usually not counted. Pumps in a process unit that has been shut down, even temporarily, are not active and should not be counted. Obviously, tweaking the equipment population number can bias the computed MTBR up or down.

As might be expected, the rules for counting pump repairs are even more intricate than those for counting population. Perhaps the simplest definition is based on work orders. After all, if a repair is required, a work order is written. But there are many exceptions and variations. Is packing adjustment a repair? What about lubrication, coupling checks, or adding oil to seal pots? Suppose a pump is repaired but a second failure occurs soon thereafter — would that repair be an additional one or a continuation of the first one? PIP specifically includes repairs initiated by preventive or predictive maintenance but many users do not count such maintenance as repairs. The computed MTBR is directly and strongly dependent on the rules for counting repairs.

Naturally, MTBR is based on compiling with federal, state or local regulations. These regulations can have a strong effect on pump MTBR and must be considered before using MTBR as a benchmark. Plants processing regulated fluids and having stringent national or local emission requirements are likely to have a lower pump MTBR. There are also questions about what constitutes a repair under the rules for Leak Detection and Repair. For example, suppose a “sniffer” test indicates an emission failure and the pump is cleaned in place with soapy water, re-tested and found OK. Is this a repair?

Just as there is more to an automobile than horsepower and more to a house than square footage, there is more to pump reliability than MTBR. Although it is almost irresistibly tempting to compare the MTBR at your plant to that reported by others, when you do so, remember to consider the rules used for keeping score.

- “Is it Time for an MTBR Standard?”, Gordon Buck and Jason Gondron, Pumps and Systems Magazine, 2004.

- Benchmarking of Reliability Indicators for Rotating Machinery, Process Industry Practices, IPI REEE002, March 1998.

- “Tracking Failures with Equipment Records and Databases”, Gordon Buck, Fluid Handling Systems, September, 2002.